Elite performance is built on a careful balance between stress and recovery, biology and behavior. This article translates practical lessons from applied sports science into usable guidance for endurance athletes and coaches. It covers how simulated altitude works, why erythropoiesis is not as simple as “more red blood cells = better,” how heat affects different race distances in surprising ways, and how the power-duration relationship and critical power model explain fatigue and pacing in surgy race environments.

Table of Contents

- Overview: three pillars of performance planning

- How simulated altitude (normobaric hypoxia) rooms work

- Erythropoiesis, hematocrit, and total hemoglobin mass

- Preconditions for getting a positive altitude response

- How to plan altitude exposure so it pays off

- Heat stress and acclimation: why shorter, harder efforts can feel hotter

- Pacing, perception, and the role of the brain

- Power-duration relationships: the roots of pacing and fatigue

- VO2 kinetics, fiber recruitment, and inefficiency during fatigue

- Running power and the current state of wearable stride meters

- Practical recommendations for coaches and athletes

- Monitoring and testing — what to measure

- Putting it together: an example timeline for a 4-week altitude/heat block

- Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

- Final lessons for training smarter, not just harder

- How long should an altitude camp be to reliably increase total hemoglobin mass?

- Can simulated altitude (normobaric hypoxia) replace real altitude?

- What are the most important preconditions before starting an altitude camp?

- How does heat affect different race distances?

- What is critical power and why should coaches measure it?

- How should pacing change in hot conditions?

- Are running power meters as reliable as cycling power meters?

- What simple daily checks can an athlete perform during altitude or heat camps?

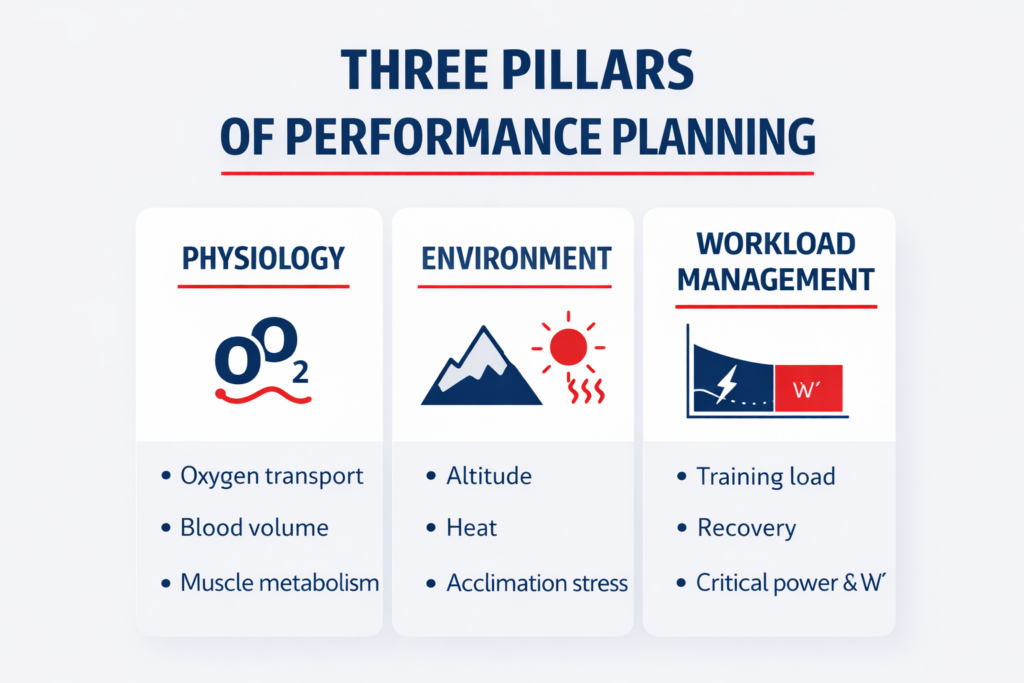

Overview: three pillars of performance planning

High-performance preparation often rests on three interconnected pillars:

- Physiology — the oxygen transport system, blood volume, and muscle metabolism.

- Environment — altitude and heat create different types of physiological stress and demand specific acclimation strategies.

- Workload management — training load, recovery and the dynamics of intensity (critical power and W prime) determine whether adaptations occur.

Understanding how those pillars interact is the difference between paying for a camp and actually getting a biological gain that translates to faster racing.

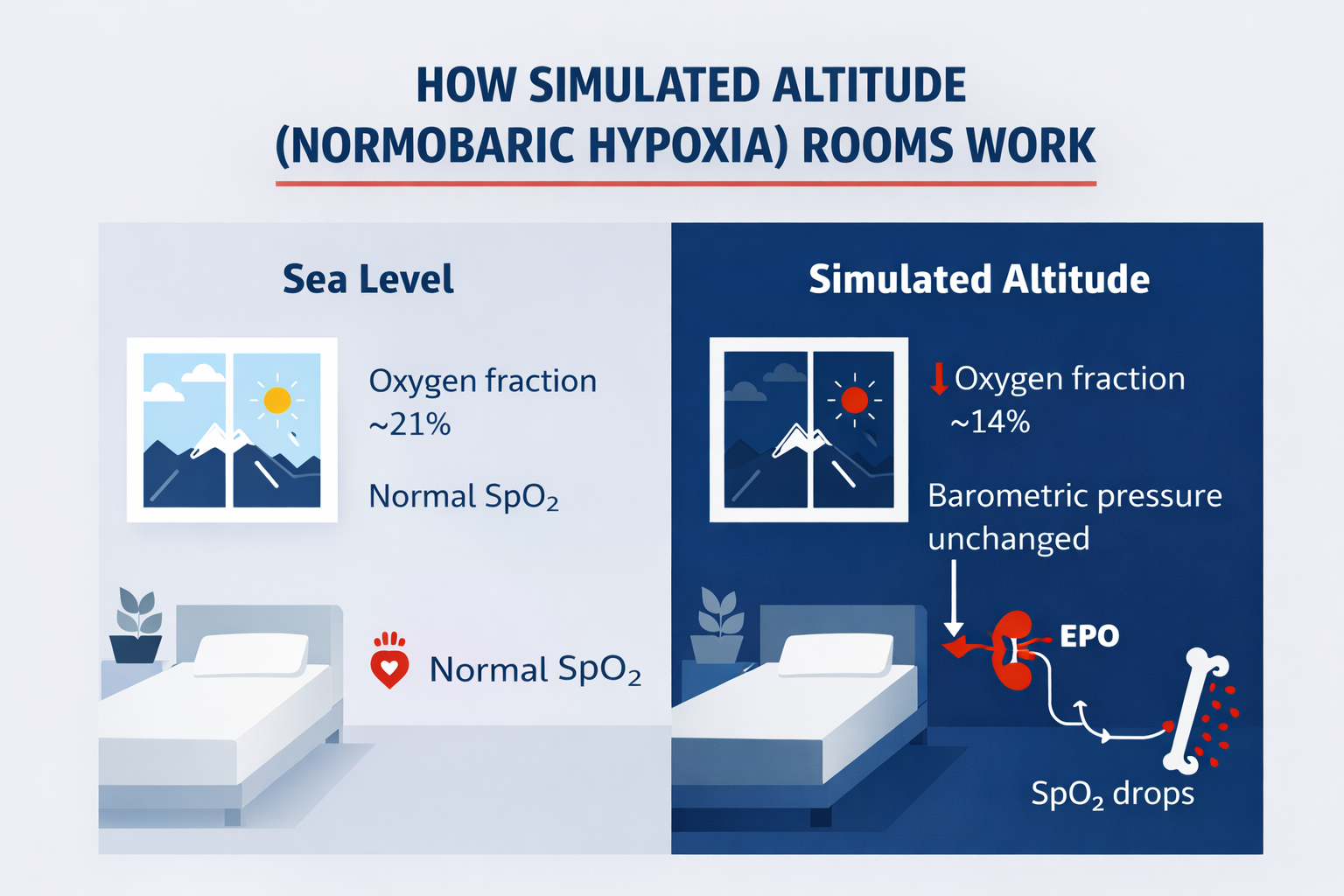

How simulated altitude (normobaric hypoxia) rooms work

Modern sport medicine centers often use altitude dormitories to simulate the oxygen environment of high altitude while staying at sea level. These rooms lower the fraction of inspired oxygen rather than reducing barometric pressure, a method called normobaric hypoxia.

In practice the facility pumps extra nitrogen into the room air to displace oxygen. The pressure stays the same as at sea level, but the percentage of oxygen is reduced. Coaches and practitioners monitor athletes with pulse oximetry and adjust the oxygen fraction to achieve target oxygen saturation levels that are known to stimulate red blood cell production.

In practice the facility pumps extra nitrogen into the room air to displace oxygen. The pressure stays the same as at sea level, but the percentage of oxygen is reduced. Coaches and practitioners monitor athletes with pulse oximetry and adjust the oxygen fraction to achieve target oxygen saturation levels that are known to stimulate red blood cell production.

What the simulation aims to trigger

The main physiological target is the stimulation of erythropoiesis — the process of manufacturing new red blood cells. The idea is to create a hypoxic stimulus strong enough to signal the kidneys and bone marrow to raise total hemoglobin mass over weeks.

Two practical points to remember:

- Simulation differs from true altitude. At real altitude barometric pressure and oxygen partial pressure both fall, whereas in normobaric rooms only oxygen fraction changes.

- Monitoring matters. Pulse oximetry provides a quick check on how the athlete is responding; hemoglobin mass tests measure whether the biological adaptation has occurred.

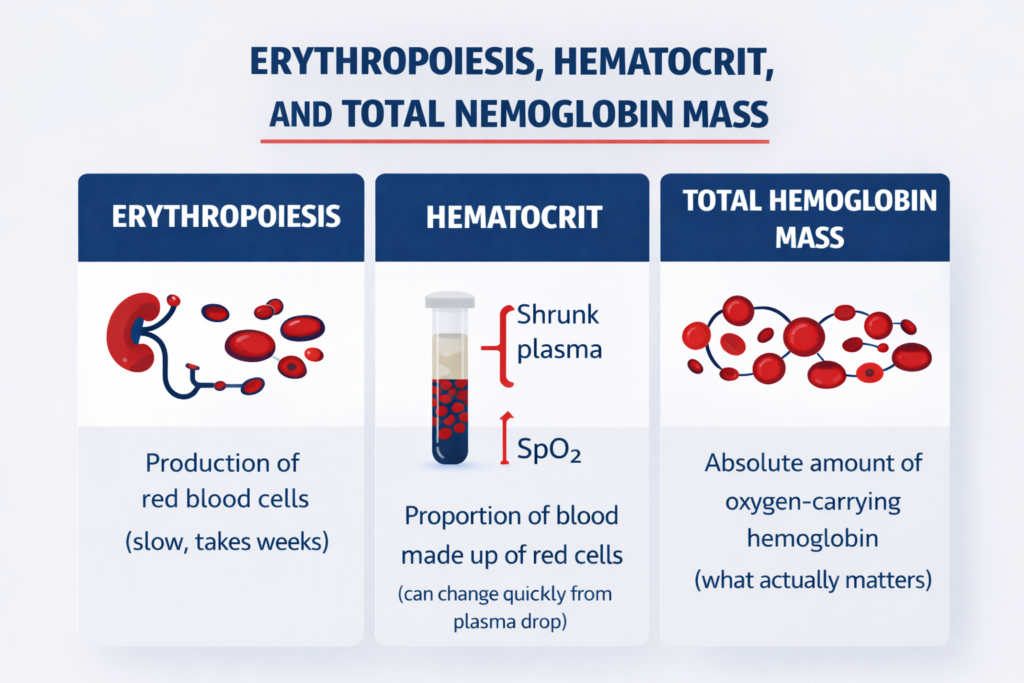

Erythropoiesis, hematocrit, and total hemoglobin mass

These three terms are often used interchangeably in casual conversation, but they describe different things and lead to different decisions.

- Erythropoiesis is the production of red blood cells in bone marrow. It takes days to weeks to materially increase red cell mass.

- Hematocrit is the percentage of whole blood made up by red blood cells. This number can change quickly because plasma volume can fluctuate rapidly.

- Total hemoglobin mass is the absolute amount of hemoglobin in the circulation and is the functional parameter for oxygen transport.

When athletes arrive at altitude they often show a quick rise in hematocrit. That rise is usually not from new red blood cells but from a loss of plasma volume through diuresis. The body reduces plasma volume as a short-term response, which raises the hematocrit percentage before erythropoiesis can increase the absolute red cell mass.

This plasma-volume drop is a normal and expected early adaptation. It is not necessarily harmful if hydration and recovery are managed, but it means hematocrit alone is an imperfect indicator of meaningful performance-relevant adaptation.

Why more red cells are not always better

Beyond a certain point the thickening of blood becomes counterproductive. Artificial methods—such as synthetic EPO or blood transfusions—can push hematocrit and hemoglobin mass high enough to impair flow and raise viscosity, which can reduce oxygen delivery and increase health risk. Practical altitude strategies aim for physiological, sustainable increases in total hemoglobin mass while keeping hematocrit within safe ranges.

Preconditions for getting a positive altitude response

Not every athlete responds the same way to altitude. Practical experience shows recurring themes that predict success or failure:

- Iron status — athletes must arrive with adequate iron stores. Iron is the limiting substrate for hemoglobin synthesis; if the body is iron-depleted the erythropoietic response is blunted.

- Health — illness during the camp tends to prevent meaningful erythropoietic gains. Respiratory infections, gastrointestinal upset, and other illnesses derail adaptation and training.

- Training load and fatigue — entering camp already in a state of chronic fatigue or overreach decreases the chance of adaptation. Adding altitude stress on top of systemic fatigue is often counterproductive.

- Duration and exposure pattern — time spent under hypoxic stress matters. Short daytime-only exposure with sea-level sleeping often gives less adaptation than longer or continuous exposures.

A recurring practical lesson is that altitude is an additional physiological stress. If training, work, travel, sleep disruption, or illness are already stressing the athlete, the altitude stimulus is less likely to produce the intended biological change.

How to plan altitude exposure so it pays off

Planning altitude exposure involves both timing and dose. The following practices help tilt the odds of success:

- Pre-check iron and health — screen iron status before travel and correct deficiencies. Treat infections and avoid travel while unwell.

- Place the camp within a coherent mesocycle — altitude camps should fit a pre-planned training block. Avoid using the camp as an opportunity for an abrupt spike in workload.

- Allow a freshening-up week — a short reduced-load week before altitude helps athletes start a camp rested, not overreached.

- Plan sufficient time — three weeks is often better than two; four weeks is better than three. Short exposure windows can produce performance changes but are less consistent for raising total hemoglobin mass.

- Use live high, train low where appropriate — alternating exposure patterns can let athletes train at higher intensities while still getting a hypoxic living stimulus.

One of the clearest practical failures comes when athletes arrive on camp already in an overreached state and then try to add even more load. The result can be performance gains from the concentrated training but no measurable increase in hemoglobin mass.

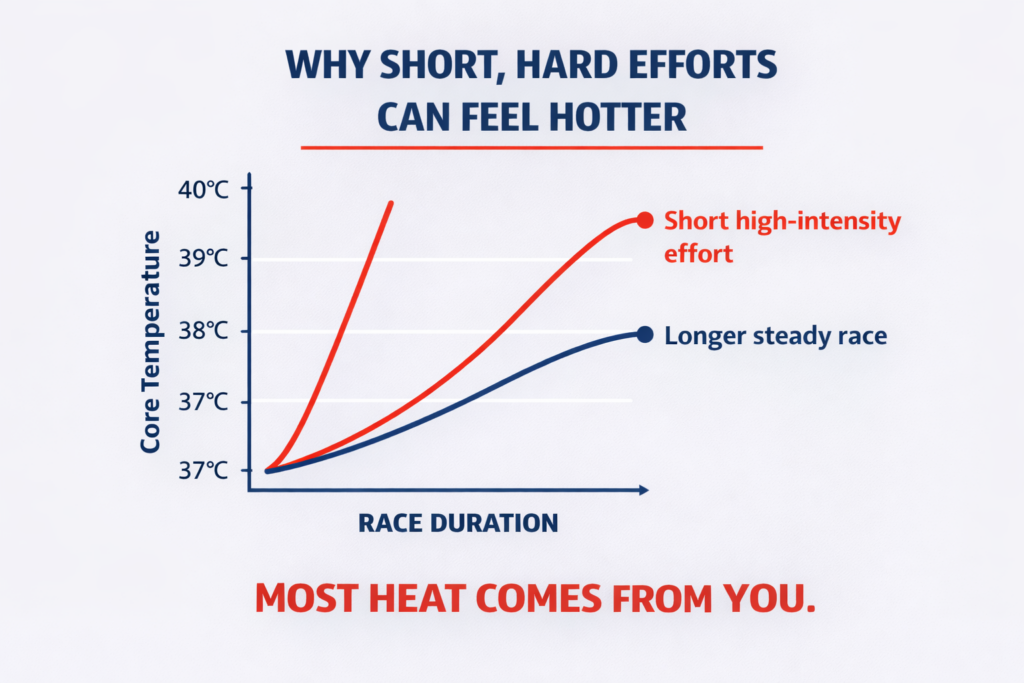

Heat stress and acclimation: why shorter, harder efforts can feel hotter

Hot and humid competition environments provide a different problem set. Heat stress is not simply about ambient temperature. The hotter the environment, the harder it is to dissipate metabolically generated heat. But a counterintuitive finding emerges from applied monitoring:

Most of the heat comes from yourself.

That insight reframes how to think about heat risk. On a hot day the body is primarily burdened by the heat produced by active muscle — the more intense the effort, the more heat produced. At very high intensities the body produces so much internal heat that core temperature can rise rapidly even over a relatively short event.

Core temperature findings from real events

Monitoring core temperature with ingestible telemetry during competitions found that short, very intense efforts (such as individual time trials) can produce faster and higher increases in core temperature than longer road races. The explanation is simple: time trials are raced at higher sustained intensity, generating more metabolic heat per minute.

Practical implications:

- Shorter, higher-intensity events may produce higher core temperature than longer events — this affects pacing, hydration, and cooling strategies.

- Heat slows pacing — athletes tend to start at similar power to cool conditions, but power falls as core temperature rises and the brain downregulates output.

- Pre-acclimation matters — teams commonly perform heat acclimation training in environments similar to target competition to reduce thermal strain.

How teams prepare for hot championships

When major championships are held in persistently hot locations, teams usually employ pre-acclimation strategies:

- Travel to hot training locations in the weeks before competition, or use controlled heat exposure facilities.

- Schedule daily heat exposures for at least one to two weeks to induce cardiovascular and sweating adaptations.

- Plan competition schedules and tactics around time-of-day effects. Organizers often schedule the most heat-sensitive events at night when ambient temperatures are lower.

In heat-sensitive race distances such as the 5k–10k range at world-class intensity, expected thermal strain is high because these races combine high intensity with durations long enough that the cumulative heat load matters.

Pacing, perception, and the role of the brain

As core temperature rises, the body sends multiple signals to the central nervous system. Those signals change perception of effort and can force involuntary reductions in output. In practice, athletes will often perceive they are pushing as hard as ever even as power or speed declines. That mismatch contributes to the common experience of starting strongly in hot conditions and fading despite perceived effort being constant.

Power-duration relationships: the roots of pacing and fatigue

Understanding how sustainable intensity relates to duration helps coaches quantify effort and design pacing strategies. The power-duration relationship is a long-studied concept. When plotted as maximal sustainable intensity versus time, the curve typically shows a steep decline from very short durations before leveling toward a long-duration asymptote.

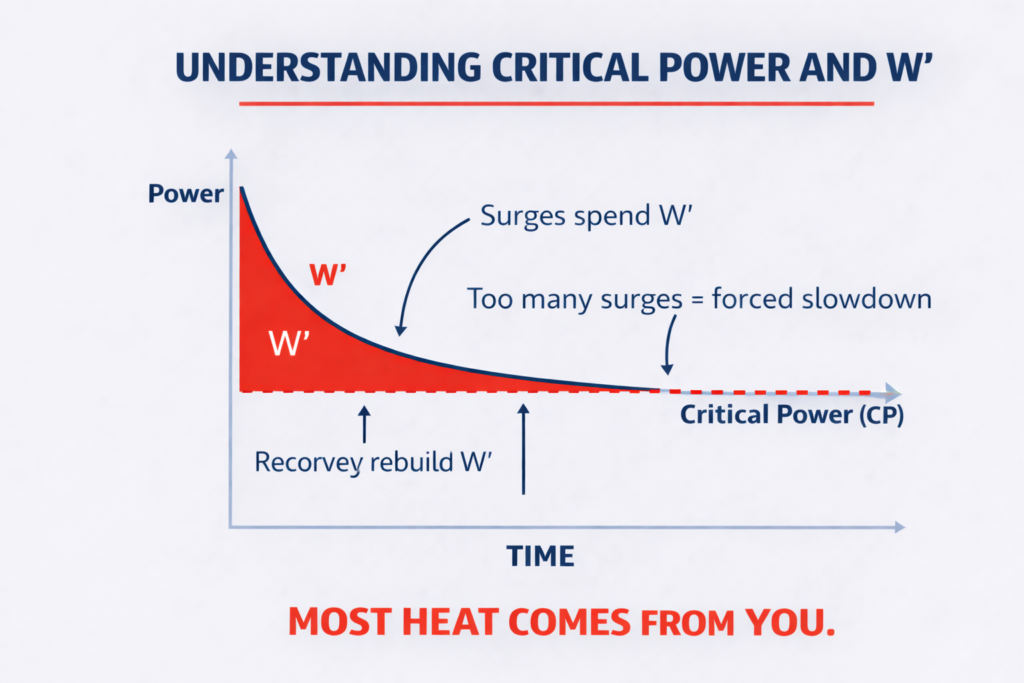

A practical and widely used mathematical model of that curve is the critical power model. It decomposes the curve into two components:

- Critical power (CP) — the asymptote of the curve representing the highest sustainable steady-state aerobic intensity over the relevant time window.

- W prime (W’) — a finite energy buffer representing the short-term anaerobic work capacity that can be expended above CP.

This view helps explain how surges in a race consume a finite anaerobic reserve and force recovery periods for the buffer to reconstitute. The stochastic power profile of road races — repeated attacks and tempo changes — drains W’ in bursts. Recovery between those bursts lets the rider or runner replenish some of the W’ through aerobic processes, but when the buffer is exhausted, sustained high intensity becomes impossible.

This view helps explain how surges in a race consume a finite anaerobic reserve and force recovery periods for the buffer to reconstitute. The stochastic power profile of road races — repeated attacks and tempo changes — drains W’ in bursts. Recovery between those bursts lets the rider or runner replenish some of the W’ through aerobic processes, but when the buffer is exhausted, sustained high intensity becomes impossible.

How critical power is estimated

Estimating CP and W’ typically involves a set of maximal efforts of differing durations and a curve fit to the resulting power-duration points. Once measured and validated, CP provides a practical threshold for training and pacing. Being slightly below CP usually produces steady-state metabolism and relatively stable VO2, while sustained work above CP drives VO2 inexorably upward and leads to finite time-to-exhaustion.

Why variability in race power matters

Two races with the same average power can impose very different physiological loads if one has many high-power surges while the other is steady. Surging racing typically produces greater neuromuscular and metabolic fatigue even if the mean is similar. Monitoring and understanding W’ spending and recovery dynamics is therefore essential in events with repeated high-intensity efforts.

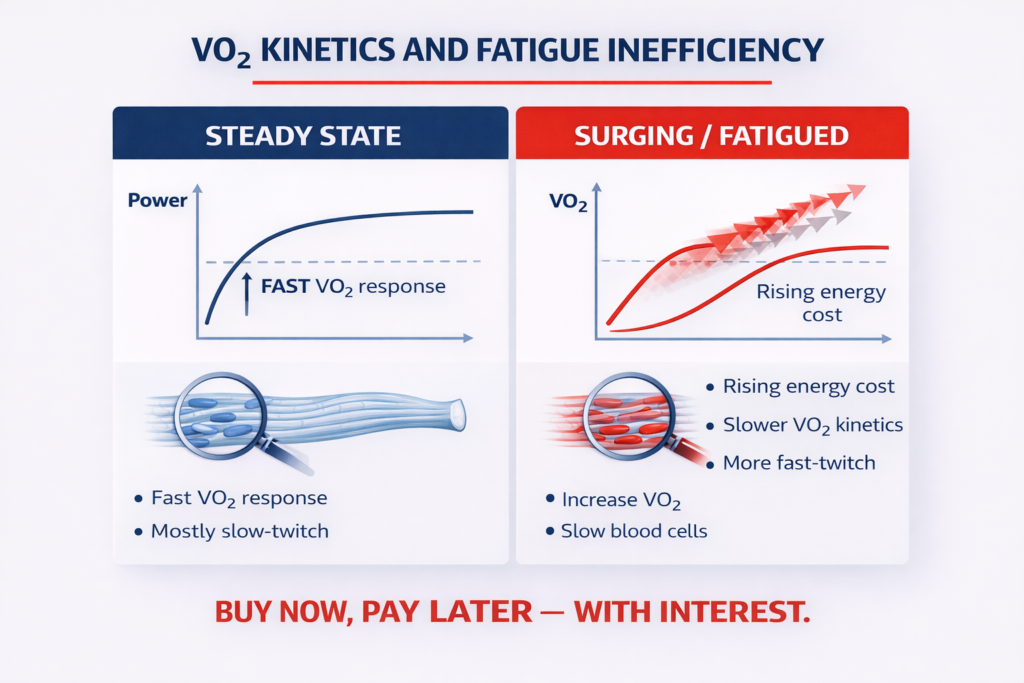

VO2 kinetics, fiber recruitment, and inefficiency during fatigue

Energy system interactions are dynamic. At low intensities, oxygen uptake kinetics are fast and small fast-twitch recruitment is minimal. That makes the aerobic system able to match demand quickly and maintain a steady state.

As intensity increases and the body recruits larger motor units and fast-twitch fibers, the time constant for VO2 response slows. The aerobic system lags more, and anaerobic processes fill the gap. Repeated or sustained use of these fast fibers creates metabolic fatigue that increases inefficiency at the muscle level. The net effect is that more energy is required to produce the same power output and the body’s ability to stabilize VO2 at high intensities fails — VO2 continues to drift up, and time to exhaustion shortens.

We perpetually do a buy-now, pay-later strategy with energy. Short surges borrow anaerobic energy and the aerobic system pays it back with a lag.

That metaphor clarifies pacing decisions. Strategic use of W’ and careful recovery between surges can keep athletes within sustainable limits for longer.

Running power and the current state of wearable stride meters

Running power devices are improving, but they have not reached the maturity and accuracy of cycling power meters yet. Running presents particular challenges: accelerometry-based devices can underestimate metabolic cost when running uphill because speed drops while work against gravity increases.

That said, power-based metrics in running and other sports are useful for revealing the stochastic nature of effort and for comparing the relative surging in d

ifferent sessions. Coaches should interpret running power with awareness of current limitations and use it together with physiological markers such as heart rate and perceived exertion.

Practical recommendations for coaches and athletes

The following checklist translates the preceding concepts into action items that reduce risk and increase the chance that a camp or preparation block will deliver performance-relevant gains.

- Pre-screen iron and health — measure iron status and address deficiencies before altitude exposure. Avoid travel if currently ill.

- Fit altitude into training periodization — altitude exposure should not coincide with the peak of a heavy overload block. A freshened athlete on arrival adapts more predictably.

- Target duration sensibly — short daytime exposures are rarely as potent as continuous multiweek stays. Three to four weeks of consistent exposure is more likely to produce hemoglobin mass gains.

- Use live high, train low where appropriate — this can allow high-quality training while still delivering a hypoxic living stimulus.

- Monitor SpO2 and symptoms — pulse oximetry provides immediate feedback, but hemoglobin mass testing is required to confirm biological change.

- Plan heat acclimation early — pre-acclimate to hot competition locations with repeated controlled exposures in the days to weeks leading to the event.

- Adjust pacing for heat — expect core temperature to rise faster in high-intensity efforts; cooling strategies and realistic pacing adjustments will help.

- Track W’ and CP — use power-duration testing to quantify CP and W’, and plan surges and recoveries so the athlete avoids unnecessary W’ depletion.

Monitoring and testing — what to measure

Useful monitoring that keeps preparation evidence-based:

- Iron indices — ferritin and full iron panel before altitude.

- Pulse oximetry — daily SpO2 checks during simulated or real altitude exposure.

- Hemoglobin mass — to quantify whether altitude exposure produced the intended red cell adaptation.

- Core temperature — ingestible sensors or other validated methods during heat testing to quantify thermal strain.

- Power-duration testing — standardized maximal efforts to derive CP and W’ and validate changes over training blocks.

- Subjective readiness and illness logs — symptoms, sleep, and perceived recovery are practical early indicators of maladaptation.

Applied monitoring reveals why two identical-looking camps can produce different outcomes. When athletes are sick, iron-depleted, or overreached, measurable adaptations in hemoglobin mass are much less likely.

Putting it together: an example timeline for a 4-week altitude/heat block

This is a template rather than a prescriptive plan. Individual variation and competition calendars dictate final desi

gn.

- Weeks -3 to -1 (preparation)

- Screen bloodwork, correct iron deficiency, treat any lingering illnesses.

- Begin tapering from any heavy overload blocks with a planned freshening week.

- If heat acclimation is necessary, begin daily controlled heat exposures in the final 10–14 days before travel.

- Week 0 (arrival and freshening)

- Arrive early enough to allow sleep and routine stabilization before heavy sessions.

- Start living in the hypoxic environment; train at planned intensities (not an abrupt increase).

-

Weeks 1–3 (adaptation phase)- Gradually increase training load as planned in the mesocycle; maintain recovery practices.

- Monitor SpO2, symptoms, and training response. Avoid piling on extra stressors like travel or unusually high workloads.

- Week 4 (return and taper)

- Return to sea level with a scheduled acclimatization return period. Use hemoglobin mass testing to verify adaptation if required.

- Begin competition-specific sharpening and tactical work.

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

- Arriving iron-deficient — check iron early and supplement under medical guidance.

- Using altitude to mask overreach — avoid combining heavy overload periods with altitude arrival; start rested.

- Short, dramatic exposure windows — daytime-only or very short stays are less consistent at raising hemoglobin mass.

- Ignoring heat intensity — treating all hot races the same is a mistake; plan cooling and pacing differently for short high-intensity events than for marathon-type efforts.

Final lessons for training smarter, not just harder

The science and field experience converge on a simple principle: an environmental intervention is only as effective as the preparation and the context that accompanies it. Altitude offers a biological stamp that can accelerate hemoglobin mass gains, but only when athletes arrive healthy, iron-replete, and not overloaded. Heat acclimation reduces thermal strain, but pace and cooling tactics must reflect how intensity drives core temperature.

Power and energy-system models help translate these physiological realities into tactical actions. Critical power and W’ quantify what the athlete can sustain and how much they can spend in surges. VO2 kinetics explain why the aerobic system takes time to “catch up” and why repeated surges cost more than a steady effort.

Applied sport science gives coaches a toolbox. The gains come from knowing which tool to use, when to use it, and how to combine tools without overloading the athlete.

How long should an altitude camp be to reliably increase total hemoglobin mass?

Short daytime-only exposures are less consistent. Multiweek camps are more effective. Practical experience shows three weeks is often better than two, and four weeks is better than three for producing reliable increases in total hemoglobin mass, assuming the athlete arrives healthy and iron-replete.

Can simulated altitude (normobaric hypoxia) replace real altitude?

Simulated altitude reduces oxygen fraction rather than barometric pressure. It can provide a similar hypoxic stimulus and is a valid tool, but it is not identical to true altitude. Both approaches can stimulate erythropoiesis when used correctly and with adequate exposure time.

What are the most important preconditions before starting an altitude camp?

Ensure athletes are healthy and not suffering from infection, and check iron status. Avoid starting a camp immediatelyy after a heavy overload or when the athlete is chronically fatigued. A freshened state on arrival optimizes the chance of biological adaptation.

How does heat affect different race distances?

Heat stress is driven primarily by internal metabolic heat from the muscles. Shorter, very high-intensity efforts can raise core temperature faster than longer lower-intensity events. Middle-range distances (for example the 5k–10k range at elite intensity) are particularly vulnerable because they combine high intensity with a long enough duration for heat to accumulate.

What is critical power and why should coaches measure it?

Critical power is the asymptote of the power-duration relationship representing the highest sustainable aerobic intensity over a useful timeframe. Measuring it and the associated W’ helps coaches quantify sustainable intensity, design pacing strategies, and understand how surges will impact performance.

How should pacing change in hot conditions?

Expect core temperature to rise faster during high-intensity bursts. Begin with conservative pacing or introduce intentional cooling strategies, and monitor signs of thermal strain. Recognize that perceived exertion may not match falling power, and adjust tactics accordingly.

Are running power meters as reliable as cycling power meters?

Running power devices are improving but are not yet as mature as cycling power meters. They can underestimate intensity on uphill running because of decreased velocity despite increased work against gravity. Use them cautiously and in combination with physiological measures like heart rate and perceived exertion.

What simple daily checks can an athlete perform during altitude or heat camps?

Daily pulse oximetry at altitude, symptom and sleep logs, monitoring perceived recovery, and basic hydration practices are practical daily checks. Periodic hemoglobin mass testing, core temperature assessments in heat trials, and periodic bloodwork for iron provide objective checkpoints.

Video of the full interview below